Another year of the Reconciliation Book Club…

Living into reconciliation has been an intentional goal of The Federation for nearly a decade and is also the foundation of our strategic plan. It is not easy. We have made mistakes and we will continue to make mistakes. But The Federation strives to change the conditions in which we are living and create more equitable relationships for and with our Indigenous partners and community members.

There are many ways that we are doing that—through our advocacy with decision-makers and outreach with sector partners, through our Transformative Reconciliation program, in our presentations to government committees, and with our new cultural safety workshops. And we are continuing to organize and host the Reconciliation Book Club, which is about to relaunch for another year.

About the Reconciliation Book Club

The idea for the Reconciliation Book Club came out of a Federation conference back in 2017. It was a response to the hesitation and fear expressed by non-Indigenous members that were keeping them from doing more to create new practices or change their relationships with Indigenous clients and communities.

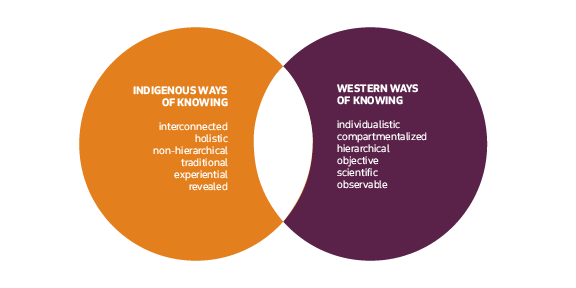

Reading and talking about Indigenous stories, histories, and ideas is one step in that direction. It’s a way to take responsibility for learning without burdening Indigenous community members with the work of teaching us. It’s a way to consider different worldviews, learn different histories, and ask (and try to answer) important questions about our work, our communities, and ourselves. Plus. purchasing these books is a direct way of supporting Indigenous artists and their families and communities—especially if you order them from an Indigenous-owned bookstore like Iron Dog Books or Massy Books.

While a book club may seem like ‘low hanging fruit’ to some, the discussions and insights and relationships are translating into real-world action. As a result of participating in the Reconciliation Book Club, some participants have found the courage and support to initiate an organization-wide Orange Shirt Day at their agency. Others initiated territorial acknowledgements for the first time. Others are altogether re-examining practices and policies relating to Indigenous clients. Some are changing how they structure and run meetings and who they contract with.

No matter where you are in your journey of reconciliation you are invited to join us. The book club meets every other month to discuss a piece of literature (fiction, non-fiction, memoir, graphic novels, poetry) by an Indigenous author in an online discussion facilitated by Federation staff. The next year of the Reconciliation Book Club will run from September 2022 through August 2023. You can register to participate on the Reconciliation Book Club website.

Books and Dates

The six books we will be reading over the next year are listed below. They were picked by past and current Book Club participants. (It’s a great list.) You can learn more about each of the books, see past books that we have read, and view upcoming dates on the Reconciliation Book Club page on our website.

| September 2022 November 2022 January 2023 March 2023 May 2023 July 2023 |

Firekeeper’s Daughter by Angeline Boulley Making Love with the Land by Joshua Whitehead The Barren Grounds by David A. Robertson My Conversations with Canadians by Lee Maracle This Place: 150 Years Retold (compilation) The Return of the Trickster by Eden Robinson |

Join us!

So come and join us. Learn about the Honourable Harvest or what it means to turn attention into intention. Struggle with us through the beautiful and challenging poetry of authors like Billy Ray Belcourt and lose yourself in some of the best YA fantasy that exists. You can participate in as many or as few sessions as you want. You can speak as much or as little as you feel comfortable.

We look forward to seeing you!