Looking at things from a different perspective

Over the past few months, I have been working on developing a new workshop to enable and support the creation of more culturally safe workplaces in the community social services sector. I want to encourage people to look at our often untold history of colonialism and help them take responsibility for choosing how to move forward along the path of reconciliation.

I was not expecting this work to have such an impact on me.

There was a lot of material to cover and incorporate. The more I read and the more I wrote, the more challenging it was. I became overwhelmed by the amount of information, the personal accounts of residential school survivors and families affected by the 60s scoop, and the ways in which the legacy of colonialism is still harming Indigenous people today.

I’ve developed workshops before. I’ve facilitated sessions like this before. This work should have been similar and straightforward, but it took me so long. I didn’t think this was going to be that difficult. And when I began presenting the workshop to my colleagues, I didn’t feel comfortable—I didn’t feel connected to the material.

It took me a while to piece together what was going on, but eventually, it struck me. I had shut off my emotional response to the material—to the history of my people. Sharing these stories had become a rote, objective process and I was presenting the material from a ‘western’ point of view. It was the history of colonization as a colonizer would tell it. I was shocked and surprised.

My goal was to create a workshop that might help and enable others to look at their own power and privilege, learn the untold history of colonization and assimilation, and understand the intergenerational trauma and stigma and racism their Indigenous clients and community members face.

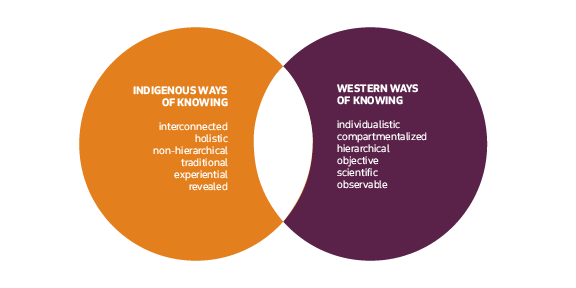

Content-wise, I had accomplished that. But in order to help people understand what an Indigenous point of view or experience might be like, I should have presented the workshop from an Indigenous perspective and explained how an Indigenous worldview is different from a western one.

It was a stark reminder of how insidious and pervasive these western attitudes and systems and cultural norms and ways of thinking are—even for non-western people. The legacy of colonization is in our laws and our values and beliefs. We all have a colonizer in our head that has never questioned the separation of humans and the natural world around us or explored why our highways are where they are or wondered whether time really is linear.

Most of us never stop and think about these things on our own. We don’t consider how and why the systems that we work and live within affect our thoughts and actions or if there are altogether different ways of viewing and moving through the world.

I live and work in a “western” country. For the most part, I watch the same movies and go to the same restaurants and shop at the same stores. So maybe it isn’t too surprising that I ended up creating a workshop about cultural safety and decolonization from the perspective of a colonizer, where western approaches and cultural norms informed the history I shared and the stories I told.

This workshop is meant to be a starting place for people wanting to begin this work. It is for people with questions, for people who may feel like they know nothing, and those who want to start creating culturally safe spaces in their organizations and communities. Doing so is important and necessary, but it requires us to look at the systems we work within from different perspectives to see how those systems were established and how we may be complicit in maintaining them. And for some people, the first step will simply be learning that there are other perspectives and ways of knowing at all.

The western world has a certain set of values, norms, and beliefs and many of us grow up assuming these are the ONLY values, norms, and beliefs. For most people, there is only one way of thinking about things like parenting, food, clothing, family roles, the seasons, time, and medicine.

For example, a common way of communicating and sharing knowledge in western society is to put a bunch of topics and bullet points in a PowerPoint slide deck and write down what we want to say. This helps us to be clear and direct; it compartmentalizes long or complex topics and gives the appearance of objectivity.

But objectivity doesn’t make something more or less true—removing the influence of feelings or opinions doesn’t make a fact or a story more legitimate. In fact, when it comes to reconciliation and cultural safety, feelings are important and necessary. That is a lesson I was taught by an elder many years ago. Speaking my truth means speaking from the heart.

That was what I failed to do when creating the first version of this workshop. And that mistake demonstrated to me how persistent and entrenched these systems and beliefs are and how easy it is to get stuck in our one familiar and comfortable way of seeing and doing things. It takes time and effort to recognize and question our own thought processes and practices. The work of decolonization and reconciliation and cultural safety can be difficult because it is so easy to slip back into the ways of knowing that we are so used to.

Is the deer crossing the road or is the road crossing the forest? Which of those perspectives feels more familiar to you? What does the water feel like to the fishes? How sure are you that time is linear? What happened to all of the histories of our country that weren’t written down?

This is a big part of what decolonization and reconciliation are all about. In order to create culturally safe spaces for Indigenous children and families, you need to be able to understand a little of their lived experience—to see from their perspective the barriers and biases and policies and practices that they face every day.

The systems we live and work within are legacies of colonization. They require and perpetuate the values and norms and worldview of colonizers. If we can’t learn to step outside our singular, dominant perspective, they will remain oppressive and biased and generate solutions and responses that are also oppressive and biased despite our best intentions.

This was a humbling experience but an important lesson.

It’s okay to make mistakes—this is hard work. But the important part will be what we do after those mistakes. Do you recognize and acknowledge where you have fallen short? Do you look for another way of doing things? Do you admit the thing you shouldn’t have said? Do you let the awkward situation pass?

Normally, an article or essay like this would conclude by returning to the opening story or reiterating the central lesson or argument. But instead, I simply encourage you to reflect on the thoughts and feelings that those questions and these ideas brought up.

Because maybe there is another way to think about this. Maybe these aren’t mistakes after all. Maybe they are lessons. Maybe they are moments of productive tension between the person we want to think we are and the person we actually are. Maybe they are opportunities to see the world from a different perspective…

Riley McKenzie

Federation Indigenous Advisor